|

(of the Suisune People)

IntroductionVillage life, religion and language are what distinguish the native people of Suisun Valley from other California Indians, and these criteria are how we identify them as Southern Patwin and not River or Hill Patwin, Miwok, Ohlone or Wappo. The links below lead to more information on the village life, religion, and language of the Suisuns and their immediate neighbors before the coming of the white man. Kroeber (1932) and McKern (1922 & 1923) are the main references for this information, and you might check them out to learn more.

|

|

Villages

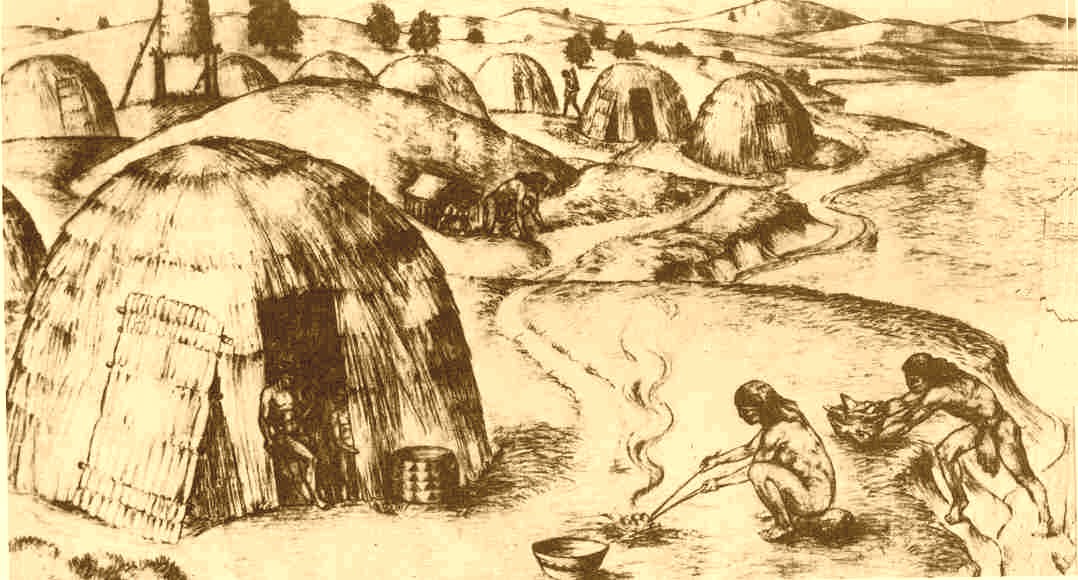

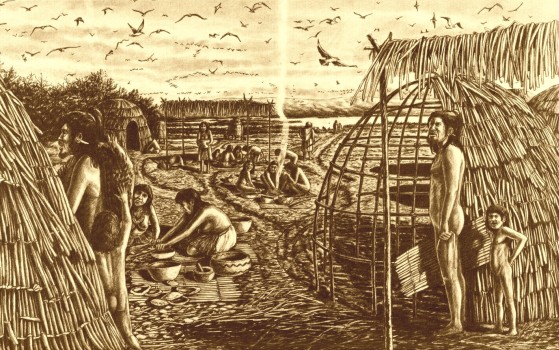

Most Patwin villages were not large, and contained maybe fifty to one-hundred people from 10 to 15 families. Large villages might be up to 300 people, and some writers suggest that in a few, very rare cases, there were villages of up to a thousand people. However, it seems more likely that such large villages were really entire tribelets made up of one or two large villages, together with several outlying, much smaller encampments dependant on the main settlements. Each family in the village had their own earth-covered hut, in which they sat out bad weather. These huts were clustered around a larger ceremonial lodge, or "roundhouse", reserved for secret dances and rituals. There was was also a smaller sweat house for the men, and a small menstrual hut for the women. The ceremonial lodges were central to what Alfred Kroeber (1925, 1932) calls the "Kuksu cult", which was a religious tradition of rituals, taboos, and dances that controlled everyday life of the Patwins. This cult also dictated rituals for boys and girls to observe at puberty to be accepted into their society as adults. Besides the main villages, there were encampments of one or more families located a short distance away. There were also temporary food-gathering camps, out in the marshes or foothills, that were only occupied temporarily in the Spring, Summer or Fall. Whereas the winter huts of the main settlements were earth-covered, those of food-gathering camps were more apt to be temporary structures of grass, bark, or bundles of sticks. (Please see our article on shelter for more information.) Professor James Bennyhoff (1977) writes that before the Spaniards came, "permanent villages were confined to natural levees and knolls along the banks of major watercourses and adjacent lakes. Tribelet centers were occupied more or less continuously for generations ... Segments of the tribelet population established seasonal camps along intermittant creeks during the spring, and temporary hunting and harvesting camps were probably set up wherever the need arose. No midden accumulations are found on the dry plains and uplands away from watercourses; though unoccupied by a resident population, this hinterland was extensively exploited by hunters and collectors of both food and raw materials. Abandoned villages retained their names and served as camp sites or temporary abodes for villages which had to move upon the death of village headmen." Though Bennyhoff (1977) writes about the Plains Miwok, this also applies to their neighbors the Southern Patwin of Suisun Valley. However, village life changed for the Patwin after the Spanish conquest, as attested to by Simpson (1847), who visited an unnamed Indian village in January of 1842 at General Mariano Vallejo's ranch in Sonoma. Some members of this community were almost certainly Suisun Indians from the Suisun Valley, who were survivors of the great small pox epidemic of 1838 that killed off most of their people. Simpson writes that, "during the day, we visited a village of General Vallejo's Indians, about three hundred in number, who were the most miserable of the race that I ever saw, excepting always the slaves of the savages of the northwest coast. Though many of them are well formed and well grown, yet every face bears the impress of poverty and wretchedness; and they are, moreover, a prey to several malignant diseases, among which an hereditary syphilis ranks as the predominant scourge alike of old and young." "They are badly clothed, badly lodged and badly fed. As to clothing, they are pretty nearly in a state of nature; as to lodging, their hovels are made of boughs wattled with bulrushes in the form of beehives, with a hole in the top for a chimney and with two holes at the bottom towards the northwest and the southeast, so as to enable the poor creatures, by closing them in turns, to exclude both the prevailing winds; and as to food, they eat the worst bullock's worst joints, with bread of acorns and chestnuts, which are most laboriously and carefully prepared by pounding and rinsing and grinding." "Though not so recognised by the law, yet they are thralls in all but the name; while, borne to the earth by the toils of civilization superadded to the privations of savage life, they vegetate rather than live, without the wish to enjoy their former pastimes or the skill to resume their former avocations. This picture, which is a correct likeness not only of General Vallejo's Indians, but of all the civilized aborigines of California, is the only remaining monument of the zeal of the church and the munificence of the state." TribeletsEach tribelet was a self-governing, politically independent band up of several families, bound to one another by ties of common language, culture and ancestry. Being members of the tribelet meant they shared ownership of a set territory, with defined boundaries, within which they made their homes, exploited the land. and defended their land from others. Though the tribelet might share identical language and customs with their neighbors, they remained separate and distinct from them. Each tribelet had one or two main villages, plus any number of much smaller, outlying encampments of one or more families. All was overseen by a hereditary headman, known to the Patwin as a "sektu", who came from the main village. However, the sektu was not an absolute ruler. Rather, he was more like the leader of a commune or co-op, in which the lands of the tribelet were equally owned by all its members, and all shared in its bounty. This sektu held his office only if the elders wished it to be so, and if he was no longer competent, or died without a male heir, they chose another sektu. The tribelet took its identity from the main village, the one where its sektu had been born. Otherwise the tribelet was nameless. However, should the sektu pass on to the spirit world without an heir, and his successor be chosen from an outlying satellite village, then most of the population moved to the village of the new sektu. Thus for a time there might be two main villages, but the village of old sektu would gradually shrink in size, and though it might eventually be abandoned, it nonetheless retained its name. Tribelets were much smaller than true tribes, which might be five or more times larger. Neighboring tribelets that spoke the same language might at times choose to form loose alliances to strengthen marital ties or wage war, but they never united into a confederation, as did the great tribes of the Old West, like the Sioux and Cheyennne. It was only after the Spanish conquest, when their way of life was changed to a struggle to survive, that tribes and chiefs became part of Patwin culture. Before then they looked to their "sektu," for guidance, or perhaps to a younger war leader, called a "yeto," to lead them in war, but there were no tribes or chiefs before the white man came.

Religion (Secret Societies of the Kuksu Cult)

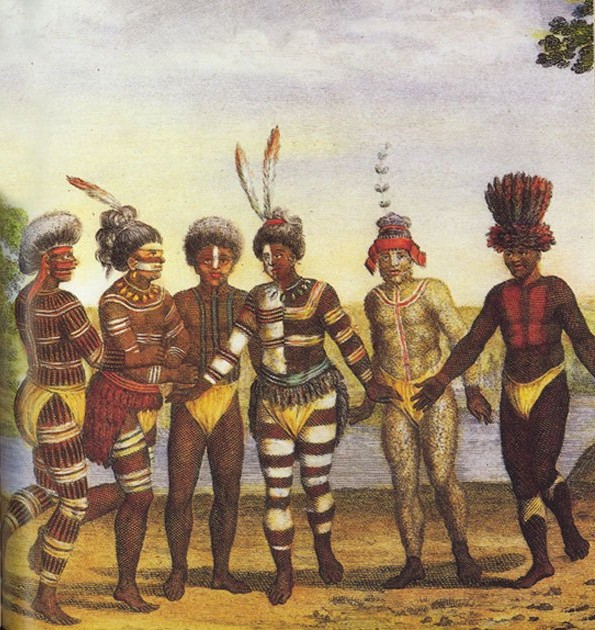

The colored print on the right, drawn about 1806 by Georg Langsdorff, shows Indian dancers at the San Jose Mission. Although the dancers shown are probably Yokut and not Southern Patwins, they are representative of what Patwin dancers may have looked like. There is also a nice 1816 drawing by Louis Choris of native dancers at the San Francisco Mission. Some dances were associated with a religion that Kroeber (1925, 1932) calls the "Kuksu cult", in which members of a male secret society performed rituals, while wearing disguises to impersonate mysterious figures from the spirit world. This cult is named for the Kuksu spirit that they impersonated most often. Many Kuksu dances, especially those associated with male puberty rites, were held in private ceremonial lodges and performed only for members of the cult. However there were also public dances held outdoors to celebrate bountiful harvests, the passing of the seasons, and so forth, as well as war dances, rain dances, and the like. These features characterize the Kuksu cult:

Guadalupe Vallejo (1890), General Vallejo's niece, writes about how the Kuksu cult changed after the Spanish came. "The California Indians were full of rude superstitions of every sort when the Franciscan fathers first began to teach them. It is hard to collect old Indian stories in these days, because they have become mixed up with what the fathers taught them. But the wild Indians a hundred years ago told the priests what they believed, and it was difficult to persuade them to give it up. In fact, there was more or less of what the fathers told them was "devil-worship" going on all the time. Rude stone altars were secretly built by the Mission Indians to "Cooksuy [Kuksu]," their dreaded god. They chose a lonely place in the hills and made piles of flat stones, five or six feet high. After that each Indian passing would throw something there, and his act of homage, called "pooish," continued until the mound was covered with a curious collection of beads, feathers, shells from the coast, and even garments and food, which no Indian dared to touch. The fathers destroyed all such altars that they could discover, and punished the Indians who worshipped there. Sometimes the more ardent followers of Cooksuy had meetings at night, slipping away from the Indian village after the retiring-bell had rung and the alcalde's rounds had been made. They prepared for the ceremony by fasting for several days; then they went to the chosen place, built a large fire, went through many dances, and called the god by a series of very strange and wild whistles, which always frightened any person who heard them. The old Indians, after being converted, told the priests that before they had seen the Spaniards come Cooksuy made his appearance from the midst of the fire in the form of a large white serpent; afterward the story was changed, and they reported that he sometimes took the form of a bull with fiery eyes."

|

|

Language

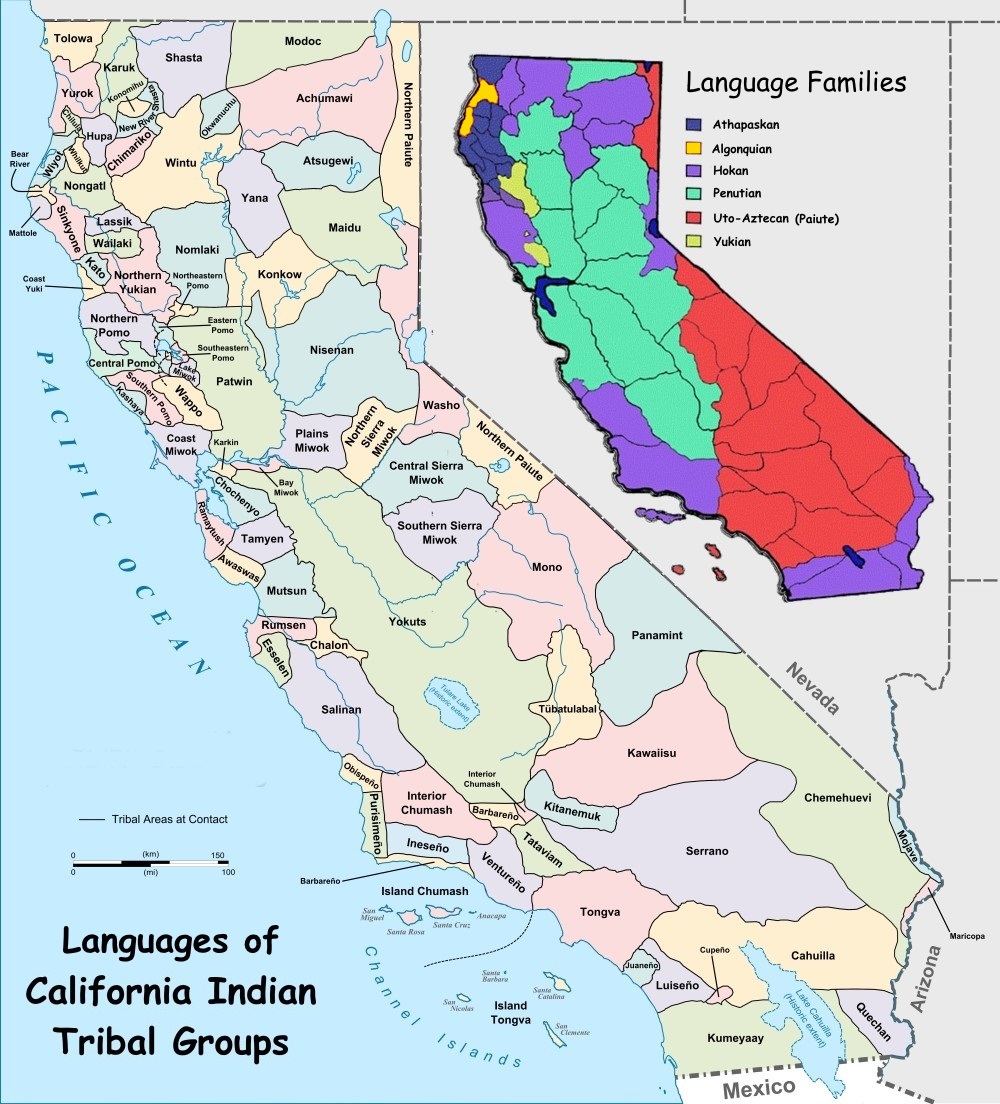

The Bay languages of Patwin, Miwok, Yokut and Ohlone belong to the Penutian language family. Also, the languages of the Wintun and Maidu, which are found in the northern Sacramento Valley, are Penutian also. Two non-Penutian languages are found in the nearby northern Napa Valley - one being Pomo, which is a Hokan language, and the other being Wappo (Guapo), which is Yukian. The Patwin tongue of the Suisun Indians, together with Wintun and Maidu, all belong to a Penutian sub-group in which the word "pen" designates the number "two". By contrast, Miwok, Ohlone and Yokut belong to a different Penutian sub-group in which "utia" is the word that designates the number "two". There is a chart below that shows these relationships. These languages are different enough from each other that speakers of one would not have been able to easily understand speakers of the other. We are not linguists, but to give some examples, we can probably compare these Indian languages to some modern European languages. For eample, the Patwin language of the Suisun Indians is perhaps as different from Wintun as French is from Italian, and as different from Maidu as French is from Spanish. Then Patwin is perhaps as different from Miwok as French is from Romanian, and as different from Wappo (Guapo), which is a Yukian tongue, as French is from Greek. There are three different dialects of the Patwin language, each dialect differing from the others by slightly different pronounciations. However, the words are not so different as to limit the speaker of one dialect from understanding the speaker of another. The Suisune and their immediate Patwin neighbors spoke the Southern Patwin dialect, whereas Patwins to the far north of them spoke Hill Patwin and those living along the Sacramento River, such as the Yolos, spoke River Patwin. The Miwok villages of the Ompins, Chupcans, Bolbones (Volvon) and others, who lived just south of the Suisune, spoke the Bay Miwok dialect of the Miwok language, whereas various other Miwoks spoke either the Coast Miwok, Plains Miwok or Sierra Miwok dialects of the same language. The Southern Patwin dialect became extinct in the 1920s when the last of the native speakers died. Possibly the last person to understand the language was Dr. Platon Vallejo (d. 1925), the son of General Mariano Vallejo, who of course was not Patwin, but Spanish. However, Platon was taught the Suisun language as a boy by his companion and mentor the Suisun Indian Tomo (d. c.1860). He compiled vocabulary lists of Suisun words, and it is from these lists that various authors over the years have tried to assign meanings to place names believed to be of Suisun Indian origin. One of Platon Vallejo's word lists is reproduced in Kroeber (1932), which is available in the link below. He also lists a few Suisun words in his 1914 article "Memoirs of the Vallejos".

|